Abstract: Cognitive flexibility is an executive function playing an important role in problem solving and the adaptation to contextual changes. While most studies investigated the contribution of cognitive flexibility to solve problems in the physical domain, the current study on baboons (Papio papio) investigated its contribution to sociality. The current study verified whether there is a relationship between cognitive flexibility at the individual level and the position of the individuals within their social group. Our study re-analysed for that purpose an already published dataset of 18 baboons Guinea baboons tested over two years in an adaptation of the Wisconsin Card Sorting task. The dominance rank and social network were inferred from their free access to the computer test system on which the cognitive task was presented. We found no clear-cut relationship between the hierarchical rank and cognitive flexibility (perseveration, learning latency and response time). By contrast, the most central baboons in their social network are those with the best performance in terms of cognitive flexibility. Overall, this study confirms our hypothesis that cognitive flexibility plays some roles in the regulation of the social relationship in baboons.

Category: Social cognition

Guinea baboons are strategic cooperators

Abstract: Humans are strategic cooperators; we make decisions on the basis of costs and benefits to maintain high levels of cooperation, and this is thought to have played a key role in human evolution. In comparison, monkeys and apes might lack the cognitive capacities necessary to develop flexible forms of cooperation. We show that Guinea baboons (Papio papio) can use direct reciprocity and partner choice to develop and maintain high levels of cooperation in a prosocial choice task. Our findings demonstrate that monkeys have the cognitive capacities to adjust their level of cooperation strategically using a combination of partner choice and partner control strategies. Such capacities were likely present in our common ancestor and would have provided the foundations for the evolution of typically human forms of cooperation.

Human and animal dominance hierarchies show a pyramidal structure guiding adult and infant social inferences

Abstract: This study investigates the structure of social hierarchies. We hypothesized that if social dominance relations serve to regulate conflicts over resources, then hierarchies should converge towards pyramidal shapes. Structural analyses and simulations confirmed this hypothesis, revealing a triadic-pyramidal motif across human and non-human hierarchies (114 species). Phylogenetic analyses showed that this pyramidal motif is widespread, with little influence of group size or phylogeny. Furthermore, nine experiments conducted in France found that human adults (N = 120) and infants (N = 120) draw inferences about dominance relations that are consistent with hierarchies’ pyramidal motif. By contrast, human participants do not draw equivalent inferences based on a tree-shaped pattern with a similar complexity to pyramids. In short, social hierarchies exhibit a pyramidal motif across a wide range of species and environments. From infancy, humans exploit this regularity to draw systematic inferences about unobserved dominance relations, using processes akin to formal reasoning.

The experimental emergence of convention in a non-human primate

Abstract: Conventions form an essential part of human social and cultural behaviour and may also be important to other animal societies. Yet, despite the wealth of evidence that has accumulated for culture in non-human animals, we know surprisingly little about non-human conventions beyond a few rare examples. We follow the literature in behavioural ecology and evolution and define conventions as systematic behaviours that solve a coordination problem in which two or more individuals need to display complementary behaviour to obtain a mutually beneficial outcome. We start by discussing the literature on conventions in non-human primates from this perspective and conclude that all the ingredients for conventions to emerge are present and therefore that they ought to be more frequently observed. We then probe the emergence of conventions by using a unique novel experimental system in which pairs of Guinea baboons (Papio papio) can voluntarily participate together in touchscreen-based cognitive testing and we show that conventions readily emerge in our experimental set-up and that they share three fundamental properties of human conventions (arbitrariness, stability and efficiency). These results question the idea that observational learning, and imitation in particular, is necessary to establish conventions; they suggest that positive reinforcement is enough.

Does discussion make crowds any wiser?

Abstract: Does discussion in large groups help or hinder the wisdom of crowds? To give rise to the wisdom of crowds, by which large groups can yield surprisingly accurate answers, aggregation mechanisms such as averaging of opinions or majority voting rely on diversity of opinions, and independence between the voters. Discussion tends to reduce diversity and independence. On the other hand, discussion in small groups has been shown to improve the accuracy of individual answers. To test the effects of discussion in large groups, we gave groups of participants (N = 1958 participants in groups of size ranging from 22 to 212; mean 59) one of three types of problems (demonstrative, factual, ethical) to solve, first individually, and then through discussion. For demonstrative (logical or mathematical) problems, discussion improved individual answers, as well as the answers reached through aggregation. For factual problems, discussion improved individual answers, and either improved or had no effect on the answers reached through aggregation. Our results suggest that, for problems which have a correct answer, discussion in large groups does not detract from the effects of the wisdom of crowds, and tends on the contrary to improve on it.

Computerized assessment of dominance hierarchy in baboons (Papio papio)

Abstract: Dominance hierarchies are an important aspect of Primate social life, and there is an increasing need to develop new systems to collect social information automatically. The main goal of this research was to explore the possibility to infer the dominance hierarchy of a group of Guinea baboons (Papio papio) from the analysis of their spontaneous interactions with freely accessible automated learning devices for monkeys (ALDM, Fagot & Bonté Behavior Research Methods, 42, 507–516, 2010). Experiment 1 compared the dominance hierarchy obtained from conventional observations of agonistic behaviours to the one inferred from the analysis of automatically recorded supplanting behaviours within the ALDM workstations. The comparison, applied to three different datasets, shows that the dominance hierarchies obtained with the two methods are highly congruent (all rs ≥ 0.75). Experiment 2 investigated the experimental potential of inferring dominance hierarchy from ALDM testing. ALDM data previously published in Goujon and Fagot (Behavioural Brain Research, 247, 101–109, 2013) were re-analysed for that purpose. Results indicate that supplanting events within the workstations lead to a transient improvement of cognitive performance for the baboon supplanting its partners and that this improvement depends on the difference in rank between the two baboons. This study therefore opens new perspectives for cognitive studies conducted in a social context.

It happened to a friend of a friend: inaccurate source reporting in rumour diffusion

Abstract: People often attribute rumours to an individual in a knowledgeable position two steps removed from them (a credible friend of a friend), such as ‘my friend’s father, who’s a cop, told me about a serial killer in town’. Little is known about the influence of such attributions on rumour propagation, or how they are maintained when the rumour is transmitted. In four studies (N = 1824) participants exposed to a rumour and asked to transmit it overwhelmingly attributed it either to a credible friend of a friend, or to a generic friend (e.g. ‘a friend told me about a serial killer in town’). In both cases, participants engaged in source shortening: e.g. when told by a friend that ‘a friend told me …’ they shared the rumour as coming from ‘a friend’ instead of ‘a friend of friend’. Source shortening and reliance on credible sources boosted rumour propagation by increasing the rumours’ perceived plausibility and participants’ willingness to share them. Models show that, in linear transmission chains, the generic friend attribution dominates, but that allowing each individual to be exposed to the rumour from several sources enables the maintenance of the credible friend of a friend attribution.

Baboons living in larger social groups have bigger brains

Abstract: The evolutionary origin of Primates’ exceptionally large brains is still highly debated. Two competing explanations have received much support: the ecological hypothesis and the social brain hypothesis (SBH). We tested the validity of the SBH in (n=82) baboons (Papio anubis) belonging to the same research centre but housed in groups with size ranging from 2 to 63 individuals. We found that baboons living in larger social groups had larger brains. This effect was driven mainly by white matter volume and to a lesser extent by grey matter volume but not by the cerebrospinal fluid. In comparison, the size of the enclosure, an ecological variable, had no such effect. In contrast to the current re-emphasis on potential ecological drivers of primate brain evolution, the present study provides renewed support for the social brain hypothesis and suggests that the social brain plastically responds to group size. Many factors may well influence brain size, yet accumulating evidence demonstrates that the complexity of social life is an important determinant of brain size in primates.

Action-matching biases in monkeys

Abstract: Stimulus–response (S–R) compatibility effects occur when observing certain stimuli facilitate the performance of a related response and interfere with performing an incompatible or different response. Using stimulus–response action pairings, this phenomenon has been used to study imitation effects in humans, and here we use a similar procedure to examine imitative biases in nonhuman primates. Eight capuchin monkeys (Sapajus spp.) were trained to perform hand and mouth actions in a stimulus–response compatibility task. Monkeys rewarded for performing a compatible action (i.e., using their hand or mouth to perform an action after observing an experimenter use the same effector) performed significantly better than those rewarded for incompatible actions (i.e., performing an action after observing an experimenter use the other effector), suggesting an initial bias for imitative action over an incompatible S–R pairing. After a predetermined number of trials, reward contingencies were reversed; that is, monkeys initially rewarded for compatible responses were now rewarded for incompatible responses, and vice versa. In this 2nd training stage, no difference in performance was identified between monkeys rewarded for compatible or incompatible actions, suggesting any imitative biases were now absent. In a 2nd experiment, 2 monkeys learned both compatible and incompatible reward contingencies in a series of learning reversals. Overall, no difference in performance ability could be attributed to the type of rule (compatible–incompatible) being rewarded. Together, these results suggest that monkeys exhibit a weak bias toward action copying, which (in line with findings from humans) can largely be eliminated through counterimitative experience.

Other better vs. self better in baboons

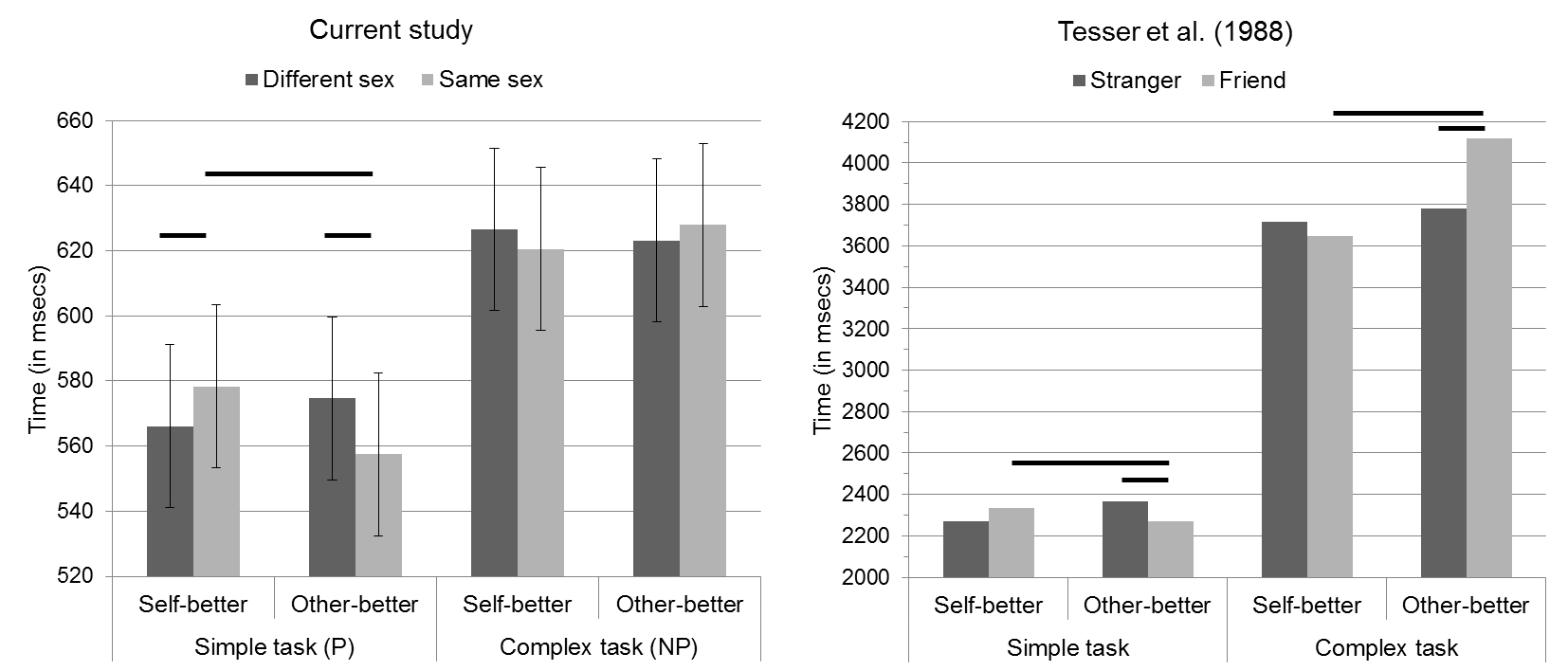

Abstract: Comparing oneself with others is an important characteristic of human social life, but the link between human and non-human forms of social comparison remains largely unknown. The present study used a computerized task presented in a social context to explore psychological mechanisms supporting social comparison in baboons and compare major findings with those usually observed in humans. We found that the effects of social comparison on subject’s performance were guided both by similarity (same vs different sex) and task complexity. Comparing oneself with a better off other (upward comparison) increased performance when the other was similar rather than dissimilar, and a reverse effect was obtained when the self was better (downward comparison). Furthermore, when the other was similar, upward comparison led to a better performance than downward comparison. Interestingly, the beneficial effect of upward comparison on baboons’ performance was only observed during simple task. Our results support the hypothesis of shared social comparison mechanisms in human and nonhuman primates.

Figure 2. (a) Estimated differences in reaction times from the averaged model for the three explanatory variables, task complexity (simple versus complex), comparison (downward/self better versus upward/other better) and similarity (same sex versus different sex). Error bars represent standard errors. Horizontal bars indicate a significant difference between the two conditions. (b) For comparison purposes, this graph illustrates the main results of Tesser et al.’s study on social comparison effects in humans [8].

Emotion-Cognition Interaction in Nonhuman Primates

Abstract: It is well established that emotion and cognition interact in humans, but such an interaction has not been extensively studied in nonhuman primates. We investigated whether emotional value can affect nonhuman primates’ processing of stimuli that are only mentally represented, not visually available. In a short-term memory task, baboons memorized the location of two target squares of the same color, which were presented with a distractor of a different color. Through prior long-term conditioning, one of the two colors had acquired a negative valence. Subjects were slower and less accurate on the memory task when the targets were negative than when they were neutral. In contrast, subjects were faster and more accurate when the distractors were negative than when they were neutral. Some of these effects were modulated by individual differences in emotional disposition. Overall, the results reveal a pattern of cognitive avoidance of negative stimuli, and show that emotional value alters cognitive processing in baboons even when the stimuli are not physically present. This suggests that emotional influences on cognition are deeply rooted in evolutionary continuity.