See comment by Cecilia Heyes, “The cognitive reality of causal understanding” and our reply “Technical reasoning: neither cognitive instinct nor cognitive gadget“.

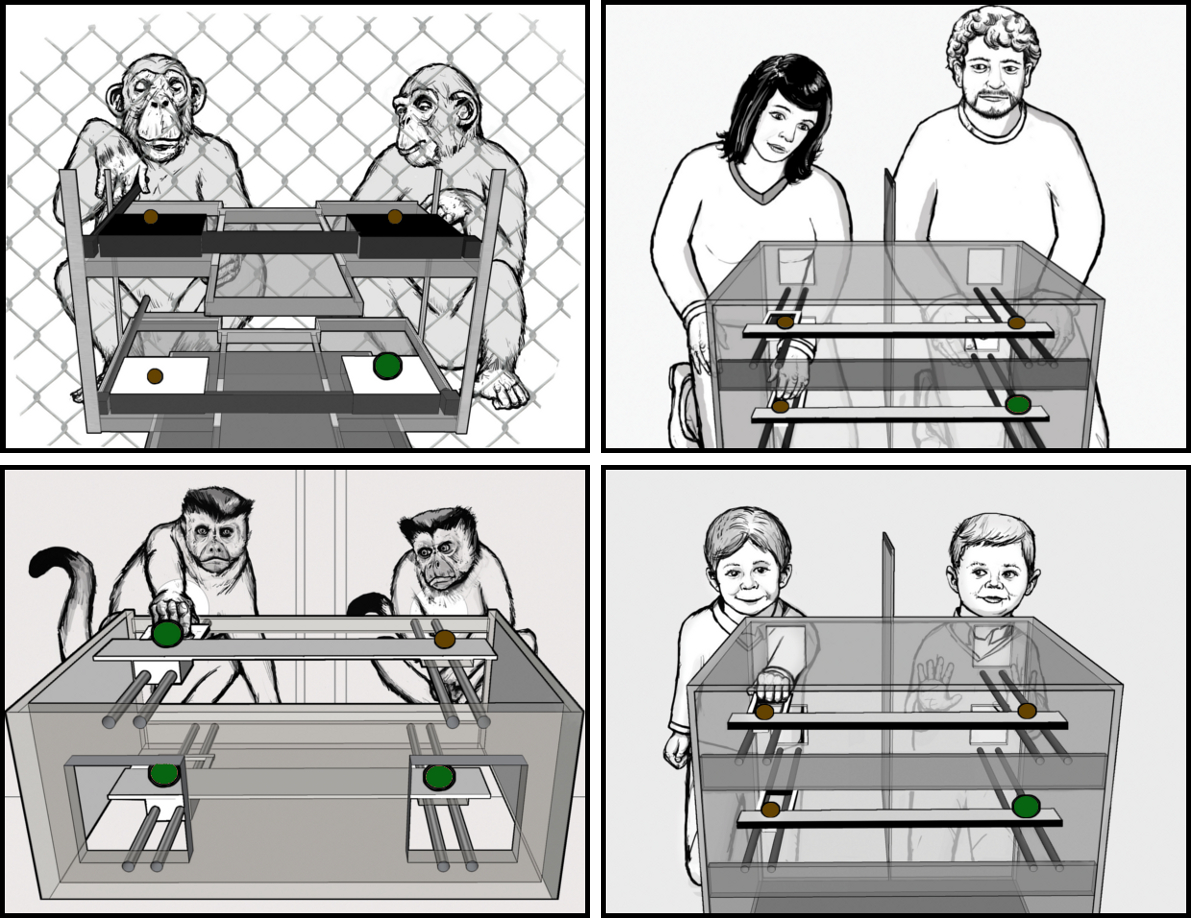

Abstract: The dominant view of cumulative technological culture suggests that high-fidelity transmission rests upon a high-fidelity copying ability, which allows individuals to reproduce the tool-use actions performed by others without needing to understand them (i.e., without causal reasoning). The opposition between copying versus reasoning is well accepted but with little supporting evidence. In this article, we investigate this distinction by examining the cognitive science literature on tool use. Evidence indicates that the ability to reproduce others’ tool-use actions requires causal understanding, which questions the copying versus reasoning distinction and the cognitive reality of the so-called copying ability. We conclude that new insights might be gained by considering causal understanding as a key driver of cumulative technological culture.

Claidière, N., Smith, K., Kirby, S., & Fagot, J. (2014). Cultural evolution of systematically structured behaviour in a non-human primate. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1797). doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1541

Claidière, N., Smith, K., Kirby, S., & Fagot, J. (2014). Cultural evolution of systematically structured behaviour in a non-human primate. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1797). doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1541 Claidière, N., Scott-Phillips, T. C., & Sperber, D. (2014). How Darwinian is cultural evolution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0368

Claidière, N., Scott-Phillips, T. C., & Sperber, D. (2014). How Darwinian is cultural evolution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0368