Abstract: Languages describe “who is doing what to whom” by distinguishing the event roles of agent (doer) and patient (undergoer), but it is debated whether they result from nonlinguistic representations that may already exist in preverbal infants and nonhuman animals. The phenomenon of causal perception, where the subsequent movements of two objects A and B evoke the impression of A launching B, is a simple depiction of an agent-patient relation. The seminal study by Leslie and Keeble from 1987 proposed that infants of 6 months old may be able to attribute agent and patient roles to such causal displays, after they demonstrated the infants’ dishabituation upon seeing a launching event that was reversed. They introduced the idea that a role reversal had taken place upon reversing the direction of the launching event (launcher becoming launchee), but not in a noncausal temporal gap event where the agent and patient roles were not present. The present study tested this hypothesis in three different populations: 6-month-old human infants, human adults, and Guinea baboons (Papio papio). For the human infants, we applied a habituation-dishabituation design, and for the human adults and baboons, a conditional match-to-sample task. We were unable to replicate the findings of Leslie and Keeble in human infants. Similarly, we did not find evidence for an effect specific to reversing launching events in human adults and baboons. Inconsistent results across different studies call into question the role reversal paradigm for Michottean launches to study event role attribution.

Author: admin

What enables human language? A biocultural framework

Abstract: Explaining the origins of language is a key challenge in understanding ourselves as a species. We present an empirical framework that draws on synergies across fields to facilitate robust studies of language evolution. The approach is multifaceted, seeing language emergence as dependent on the

convergence of multiple capacities, each with their own evolutionary trajectories. It is explicitly biocultural, recognizing and incorporating the importance of both biological preparedness and cultural transmission as well as interactions between them. We demonstrate this approach through three

case studies that examine the evolution of different facets involved in human language (vocal production learning, linguistic structure, and social underpinnings).

Testing semantic compositionality in baboons (Papio papio) through relearning and generalization

Abstract: This study investigates whether baboons are capable of semantic compositionality, specifically, whether they can apply compositional rules to new situations (generalization). In language, semantic compositionality is linked to productivity, the generalization of a rule to new combinations. Across four experiments, baboons were trained to match visual stimuli based on either shape or color depending on symbolic cues. Experiments 1–3 tested generalization under different task complexities but consistently failed to show evidence that baboons understood or applied the matching rules beyond memorized combinations. Only in Experiment 4, which used a relearning paradigm rather than generalization, did baboons show improved performance when the rule remained consistent across phases. Four hypotheses were explored to explain the lack of generalization: an iconicity-novelty bias, the possibility that compositionality is present, but that training was not sufficient for generalization, rote memorization of cue-sample pairs, and a difference between implicit and explicit learning. The findings do not allow us to discriminate between these hypotheses.

Agent Preference in Chasing Interactions in Guinea Baboons (Papio papio): Uncovering the Roots of Subject–Object Order in Language

Abstract: Languages tend to describe “who is doing what to whom” by placing subjects before objects. This may reflect a bias for agents in event cognition: Agents capture more attention than patients in human adults and infants. We investigated whether this agent preference is shared with nonhuman animals. We presented Guinea baboons (Papio papio; N = 13) with a change-detection paradigm on chasing animations. The baboons were trained to respond to a color change that was applied to either the chaser/agent or the chasee/patient. They were faster to detect a change to the chaser than to the chasee, which could not be explained by low-level features in our stimuli such as the chaser’s motion pattern or position. An agent preference may be an evolutionarily old mechanism that is shared between humans and other primates that could have become externalized in language as a tendency to place the subject first.

Can non-human primates extract the linear trend from a noisy scatterplot?

Abstract: Recent studies showed that humans, regardless of age, education, and culture, can extract the linear trend of a noisy scatterplot. Although this capacity looks sophisticated, it may simply reflect the extraction of the principal trend of the graph, as if the cloud of dots was processed as an oriented object. To test this idea, we trained Guinea baboons to associate arbitrary shapes with the increasing or decreasing trends of noiseless and noisy scatterplots, while varying the number of points, the noise level, and the regression slope. Many baboons successfully learned this conditional match-to-sample task, and their accuracy varied as a sigmoid function of the t-value of the regression, the same statistical index upon which humans also base their answers. The perceptual component of human graphics abilities seems thus to be based on the recycling of a phylogenetically older competence of the primate visual system for extracting the principal axes of visual displays.

Cognitive flexibility and sociality in Guinea baboons (Papio papio)

Abstract: Cognitive flexibility is an executive function playing an important role in problem solving and the adaptation to contextual changes. While most studies investigated the contribution of cognitive flexibility to solve problems in the physical domain, the current study on baboons (Papio papio) investigated its contribution to sociality. The current study verified whether there is a relationship between cognitive flexibility at the individual level and the position of the individuals within their social group. Our study re-analysed for that purpose an already published dataset of 18 baboons Guinea baboons tested over two years in an adaptation of the Wisconsin Card Sorting task. The dominance rank and social network were inferred from their free access to the computer test system on which the cognitive task was presented. We found no clear-cut relationship between the hierarchical rank and cognitive flexibility (perseveration, learning latency and response time). By contrast, the most central baboons in their social network are those with the best performance in terms of cognitive flexibility. Overall, this study confirms our hypothesis that cognitive flexibility plays some roles in the regulation of the social relationship in baboons.

A comparative study of causal perception in Guinea baboons (Papio papio) and human adults

Abstract: In humans, simple 2D visual displays of launching events (“Michottean launches”) can evoke the impression of causality. Direct launching events are regarded as causal, but similar events with a temporal and/or spatial gap between the movements of the two objects, as non-causal. This ability to distinguish between causal and non-causal events is perceptual in nature and develops early and preverbally in infancy. In the present study we investigated the evolutionary origins of this phenomenon and tested whether Guinea baboons (Papio papio) perceive causality in launching events. We used a novel paradigm which was designed to distinguish between the use of causality and the use of spatiotemporal properties. Our results indicate that Guinea baboons successfully discriminate between different Michottean events, but we did not find a learning advantage for a categorisation based on causality as was the case for human adults. Our results imply that, contrary to humans, baboons focused on the spatial and temporal gaps to achieve accurate categorisation, but not on causality per se. Understanding how animals perceive causality is important to figure out whether non-human animals comprehend events similarly to humans. Our study hints at a different manner of processing physical causality for Guinea baboons and human adults.

Guinea baboons are strategic cooperators

Abstract: Humans are strategic cooperators; we make decisions on the basis of costs and benefits to maintain high levels of cooperation, and this is thought to have played a key role in human evolution. In comparison, monkeys and apes might lack the cognitive capacities necessary to develop flexible forms of cooperation. We show that Guinea baboons (Papio papio) can use direct reciprocity and partner choice to develop and maintain high levels of cooperation in a prosocial choice task. Our findings demonstrate that monkeys have the cognitive capacities to adjust their level of cooperation strategically using a combination of partner choice and partner control strategies. Such capacities were likely present in our common ancestor and would have provided the foundations for the evolution of typically human forms of cooperation.

Human and animal dominance hierarchies show a pyramidal structure guiding adult and infant social inferences

Abstract: This study investigates the structure of social hierarchies. We hypothesized that if social dominance relations serve to regulate conflicts over resources, then hierarchies should converge towards pyramidal shapes. Structural analyses and simulations confirmed this hypothesis, revealing a triadic-pyramidal motif across human and non-human hierarchies (114 species). Phylogenetic analyses showed that this pyramidal motif is widespread, with little influence of group size or phylogeny. Furthermore, nine experiments conducted in France found that human adults (N = 120) and infants (N = 120) draw inferences about dominance relations that are consistent with hierarchies’ pyramidal motif. By contrast, human participants do not draw equivalent inferences based on a tree-shaped pattern with a similar complexity to pyramids. In short, social hierarchies exhibit a pyramidal motif across a wide range of species and environments. From infancy, humans exploit this regularity to draw systematic inferences about unobserved dominance relations, using processes akin to formal reasoning.

Bringing cumulative technological culture beyond copying versus reasoning

See comment by Cecilia Heyes, “The cognitive reality of causal understanding” and our reply “Technical reasoning: neither cognitive instinct nor cognitive gadget“.

Abstract: The dominant view of cumulative technological culture suggests that high-fidelity transmission rests upon a high-fidelity copying ability, which allows individuals to reproduce the tool-use actions performed by others without needing to understand them (i.e., without causal reasoning). The opposition between copying versus reasoning is well accepted but with little supporting evidence. In this article, we investigate this distinction by examining the cognitive science literature on tool use. Evidence indicates that the ability to reproduce others’ tool-use actions requires causal understanding, which questions the copying versus reasoning distinction and the cognitive reality of the so-called copying ability. We conclude that new insights might be gained by considering causal understanding as a key driver of cumulative technological culture.

Age effect in expert cognitive flexibility in Guinea baboons (Papio papio)

Cognitive flexibility in non-human primates is traditionally measured with the conceptual set shifting task (CSST). In our laboratory, Guinea baboons (N = 24) were continuously tested with a CSST task during approximately 10 years. Our task involved the presentation of three stimuli on a touch screen all made from 3 possible colours and 3 shapes. The subjects had to touch the stimulus containing the stimulus dimension (e.g., green) that was constantly rewarded until the stimulus dimension changed. Analysis of perseveration responses, scores and response times collected during the last two years of testing (approximately 1.6 million trials) indicate (1) that the baboons have developed an “expert” form of cognitive flexibility and (2) that their performance was age-dependent, it was at a developing stage in juveniles, optimal in adults, declining in middle-aged, and strongly impaired in the oldest age group. A direct comparison with the data collected by Bonté , Flemming & Fagot (2011) on some of the same baboons and same task as in the current study indicates that (3) the performance of all age groups has improved after 10 years of training, even for the now old individuals. All these data validate the use of non-human primates as models of human cognitive flexibility and suggest that cognitive flexibility in humans has a long evolutionary history.

Probability matching is not the default decision making strategy in human and non-human primates

Abstract: Probability matching has long been taken as a prime example of irrational behaviour in human decision making; however, its nature and uniqueness in the animal world is still much debated. In this paper we report a set of four preregistered experiments testing adult humans and Guinea baboons on matched probability learning tasks, manipulating task complexity (binary or ternary prediction tasks) and reinforcement procedures (with and without corrective feedback). Our findings suggest that probability matching behaviour within primate species is restricted to humans and the simplest possible binary prediction tasks; utility-maximising is seen in more complex tasks for humans as pattern-search becomes more effortful, and we observe it across the board in baboons, altogether suggesting that it is a cognitively less demanding strategy. These results provide further evidence that neither human nor non-human primates default to probability matching; however, unlike other primates, adult humans probability match when the cost of pattern search is low.

Impact of technical reasoning and theory of mind on cumulative technological culture: insights from a model of micro-societies

Our technologies have never ceased to evolve, allowing our lineage to expand its habitat all over the Earth, and even to explore space. This phenomenon, called cumulative technological culture (CTC), has been studied extensively, notably using mathematical and computational models. However, the cognitive capacities needed for the emergence and maintenance of CTC remain largely unknown. In the literature, the focus is put on the distinctive ability of humans to imitate, with an emphasis on our unique social skills underlying it, namely theory of mind (ToM). A recent alternative view, called the technical-reasoning hypothesis, proposes that our unique ability to understand the physical world (i.e., technical reasoning; TR) might also play a critical role in CTC. Here, we propose a simple model, based on the micro-society paradigm, that integrates these two hypotheses. The model is composed of a simple environment with only one technology that is transmitted between generations of individuals. These individuals have two cognitive skills: ToM and TR, and can learn in different social-learning conditions to improve the technology. The results of the model show that TR can support both the transmission of information and the modification of the technology, and that ToM is not necessary for the emergence of CTC although it allows a faster growth rate.

Are monkeys sensitive to informativeness: An experimental study with baboons (Papio papio)

Informativeness (defined as reduction of uncertainty) is central in human communication. In the present study, we investigate baboons’ sensitivity to informativeness by manipulating the informativity of a cue relative to a response display and by allowing participants to anticipate their answers or to wait for a revealed answer (with variable delays). Our hypotheses were that anticipations would increase with informativity, while response times to revealed trials would decrease with informativity. These predictions were verified in Experiment 1. In Experiments 2 and 3, we manipulated rewards (rewarding anticipation responses at 70% only) to see whether reward tracking alone could account for the results in Experiment 1. We observed that the link between anticipations and informativeness disappeared, but not the link between informativeness and decreased RTs for revealed trials. Additionally, in all three experiments, the number of correct answers in revealed trials with fast reaction times (< 250ms) increased with informativeness. We conclude that baboons are sensitive to informativeness as an ecologically sound means to tracking reward.

The role of anointing in robust capuchin monkey, Sapajus apella, social dynamics

Anointing is a behaviour in which animals apply pungent-smelling materials over their bodies. It can be done individually or socially in contact with others. Social anointing can provide coverage of body parts inaccessible to the individual, consistent with hypotheses that propose medicinal benefits. However, in highly social capuchin monkeys, Sapajus and Cebus spp., anointing has been suggested to also benefit group members through ‘social bonding’. To test this, we used social network analysis to measure changes in proximity patterns during and shortly after anointing compared to a baseline condition. We presented two capuchin groups with varying quantities of onion, which reliably induces anointing, to create ‘rare resource’ and ‘abundant resource’ conditions. We examined the immediate and overall effects of anointing behaviour on the monkeys’ social networks, using patterns of proximity as a measure of social bonds. For one group, proximity increased significantly after anointing over baseline values for both rare and abundant resource conditions, but for the other group proximity only increased following the rare resource condition, suggesting a role in mediating social relationships. Social interactions were affected differently in the two groups, reflecting the complex nature of capuchin social organization. Although peripheral males anointed in proximity to other group members, the weak centrality only changed in one group following anointing bouts, indicating variable social responses to anointing. We suggest in part that anointing in capuchins is analogous to social grooming: both behaviours have an antiparasitic function and can be done individually or socially requiring contact between two or more individuals. We propose that they have evolved a social function within complex repertoires of social behaviours. Our alternative perspective avoids treating medicinal and social explanations as alternative hypotheses and, along with increasing support for the medical explanations for anointing, allows us to conceptualize social anointing in capuchins as ‘social medication’.

Understanding Imitation in Papio papio: The Role of Experience and the Presence of a Conspecific Demonstrator

What factors affect imitation performance? Varying theories of imitation stress the role of experience, but few studies have explicitly tested its role in imitative learning in non-human primates. We tested several predictions regarding the role of experience, conspecific presence, and action compatibility using a stimulus–response compatibility protocol. Nineteen baboons separated into two experimental groups learned to respond by targeting on a touch screen the same stimulus as their neighbor (compatible) or the opposite stimulus (incompatible). They first performed the task with a conspecific demonstrator (social phase) and then a computer demonstrator (ghost phase). After reaching a predetermined success threshold, they were then tested in an opposite compatibility condition (i.e.,reversal learning conditions). Seven baboons performed at least two reversals during the social phase, and we found no significant difference between the compatible and incompatible conditions, although we noticed slightly faster response times (RTs) in the compatible condition that disappeared after the first reversal. During the ghost phase, monkeys showed difficulties in learning the incompatible condition, and the compatible condition RTs tended to be slower than during the social phase. Together, these results suggest that (a) there is no strong movement compatibility effect in our task and that (b) the presence of a demonstrator plays a role in eliciting correct responses but is not essential as has been

previously shown in human studies.

Technical reasoning bolsters cumulative technological culture through convergent transformations

Abstract: Understanding the evolution of human technology is key to solving the mystery of our origins. Current theories propose that technology evolved through the accumulation of modifications that were mostly transmitted between individuals by blind copying and the selective retention of advantageous variations. An alternative account is that high-fidelity transmission in the context of cumulative technological culture is supported by technical reasoning, which is a reconstruction mechanism that allows individuals to converge to optimal solutions. We tested these two competing hypotheses with a microsociety experiment, in which participants had to optimize a physical system in partial- and degraded-information transmission conditions. Our results indicated an improvement of the system over generations, which was accompanied by an increased understanding of it. The solutions produced tended to progressively converge over generations. These findings show that technical reasoning can bolster high-fidelity transmission through convergent transformations, which highlights its role in the cultural evolution of technology.

Broca area homologue’s asymmetry reflects gestural communication lateralisation in monkeys (Papio anubis)

Abstract: Manual gestures and speech recruit a common neural network, involving Broca’s area in the left hemisphere. Such speech-gesture integration gave rise to theories on the critical role of manual gesturing in the origin of language. Within this evolutionary framework, research on gestural communication in our closer primate relatives has received renewed attention for investigating its potential language-like features. Here, using in-vivo anatomical MRI in 50 baboons, we found that communicative gesturing is related to Broca homologue’s marker in monkeys, namely the ventral portion of the Inferior Arcuate sulcus (IA sulcus). In fact, both direction and degree of gestural communication’s handedness – but not handedness for object manipulation – are associated and correlated with contralateral depth asymmetry at this exact IA sulcus portion. In other words, baboons that prefer to communicate with their right hand have a deeper left-than-right IA sulcus, than those preferring to communicate with their left hand and vice versa. Interestingly, in contrast to handedness for object manipulation, gestural communication’s lateralisation is not associated to the Central sulcus depth asymmetry, suggesting a double dissociation of handedness’ types between manipulative action and gestural communication. It is thus not excluded that this specific gestural lateralisation signature within the baboons’ frontal cortex might reflect a phylogenetical continuity with language-related Broca lateralisation in humans.

The experimental emergence of convention in a non-human primate

Abstract: Conventions form an essential part of human social and cultural behaviour and may also be important to other animal societies. Yet, despite the wealth of evidence that has accumulated for culture in non-human animals, we know surprisingly little about non-human conventions beyond a few rare examples. We follow the literature in behavioural ecology and evolution and define conventions as systematic behaviours that solve a coordination problem in which two or more individuals need to display complementary behaviour to obtain a mutually beneficial outcome. We start by discussing the literature on conventions in non-human primates from this perspective and conclude that all the ingredients for conventions to emerge are present and therefore that they ought to be more frequently observed. We then probe the emergence of conventions by using a unique novel experimental system in which pairs of Guinea baboons (Papio papio) can voluntarily participate together in touchscreen-based cognitive testing and we show that conventions readily emerge in our experimental set-up and that they share three fundamental properties of human conventions (arbitrariness, stability and efficiency). These results question the idea that observational learning, and imitation in particular, is necessary to establish conventions; they suggest that positive reinforcement is enough.

Does discussion make crowds any wiser?

Abstract: Does discussion in large groups help or hinder the wisdom of crowds? To give rise to the wisdom of crowds, by which large groups can yield surprisingly accurate answers, aggregation mechanisms such as averaging of opinions or majority voting rely on diversity of opinions, and independence between the voters. Discussion tends to reduce diversity and independence. On the other hand, discussion in small groups has been shown to improve the accuracy of individual answers. To test the effects of discussion in large groups, we gave groups of participants (N = 1958 participants in groups of size ranging from 22 to 212; mean 59) one of three types of problems (demonstrative, factual, ethical) to solve, first individually, and then through discussion. For demonstrative (logical or mathematical) problems, discussion improved individual answers, as well as the answers reached through aggregation. For factual problems, discussion improved individual answers, and either improved or had no effect on the answers reached through aggregation. Our results suggest that, for problems which have a correct answer, discussion in large groups does not detract from the effects of the wisdom of crowds, and tends on the contrary to improve on it.

From temporal network data to the dynamics of social relationships

Abstract: Networks are well-established representations of social systems, and temporal networks are widely used to study their dynamics. However, going from temporal network data (i.e. a stream of interactions between individuals) to a representation of the social group’s evolution remains a challenge. Indeed, the temporal network at any specific time contains only the interactions taking place at that time and aggregating on successive time-windows also has important limitations. Here, we present a new framework to study the dynamic evolution of social networks based on the idea that social relationships are interdependent: as the time we can invest in social relationships is limited, reinforcing a relationship with someone is done at the expense of our relationships with others. We implement this interdependence in a parsimonious two-parameter model and apply it to several human and non-human primates’ datasets to demonstrate that this model detects even small and short perturbations of the networks that cannot be detected using the standard technique of successive aggregated networks. Our model solves a long-standing problem by providing a simple and natural way to describe the dynamic evolution of social networks, with far-reaching consequences for the study of social networks and social evolution.

Computerized assessment of dominance hierarchy in baboons (Papio papio)

Abstract: Dominance hierarchies are an important aspect of Primate social life, and there is an increasing need to develop new systems to collect social information automatically. The main goal of this research was to explore the possibility to infer the dominance hierarchy of a group of Guinea baboons (Papio papio) from the analysis of their spontaneous interactions with freely accessible automated learning devices for monkeys (ALDM, Fagot & Bonté Behavior Research Methods, 42, 507–516, 2010). Experiment 1 compared the dominance hierarchy obtained from conventional observations of agonistic behaviours to the one inferred from the analysis of automatically recorded supplanting behaviours within the ALDM workstations. The comparison, applied to three different datasets, shows that the dominance hierarchies obtained with the two methods are highly congruent (all rs ≥ 0.75). Experiment 2 investigated the experimental potential of inferring dominance hierarchy from ALDM testing. ALDM data previously published in Goujon and Fagot (Behavioural Brain Research, 247, 101–109, 2013) were re-analysed for that purpose. Results indicate that supplanting events within the workstations lead to a transient improvement of cognitive performance for the baboon supplanting its partners and that this improvement depends on the difference in rank between the two baboons. This study therefore opens new perspectives for cognitive studies conducted in a social context.

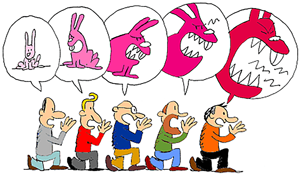

It happened to a friend of a friend: inaccurate source reporting in rumour diffusion

Abstract: People often attribute rumours to an individual in a knowledgeable position two steps removed from them (a credible friend of a friend), such as ‘my friend’s father, who’s a cop, told me about a serial killer in town’. Little is known about the influence of such attributions on rumour propagation, or how they are maintained when the rumour is transmitted. In four studies (N = 1824) participants exposed to a rumour and asked to transmit it overwhelmingly attributed it either to a credible friend of a friend, or to a generic friend (e.g. ‘a friend told me about a serial killer in town’). In both cases, participants engaged in source shortening: e.g. when told by a friend that ‘a friend told me …’ they shared the rumour as coming from ‘a friend’ instead of ‘a friend of friend’. Source shortening and reliance on credible sources boosted rumour propagation by increasing the rumours’ perceived plausibility and participants’ willingness to share them. Models show that, in linear transmission chains, the generic friend attribution dominates, but that allowing each individual to be exposed to the rumour from several sources enables the maintenance of the credible friend of a friend attribution.

Taking into account the wider evolutionary context of cumulative cultural evolution

Abstract: The target article reviews evidence showing that technological reasoning is crucial to cumulative technological culture but it fails to discuss the implications for the emergence of cumulative cultural evolution (CCE) in general. The target article supports the social view of CCE against the more ecological alternative and suggests that CCE appears when specialised individual-learning mechanisms evolve.

Link to the target article: Osiurak, F., & Reynaud, E. (2020). The elephant in the room: What matters cognitively in cumulative technological culture. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 43, E156. doi:10.1017/S0140525X19003236

Baboons living in larger social groups have bigger brains

Abstract: The evolutionary origin of Primates’ exceptionally large brains is still highly debated. Two competing explanations have received much support: the ecological hypothesis and the social brain hypothesis (SBH). We tested the validity of the SBH in (n=82) baboons (Papio anubis) belonging to the same research centre but housed in groups with size ranging from 2 to 63 individuals. We found that baboons living in larger social groups had larger brains. This effect was driven mainly by white matter volume and to a lesser extent by grey matter volume but not by the cerebrospinal fluid. In comparison, the size of the enclosure, an ecological variable, had no such effect. In contrast to the current re-emphasis on potential ecological drivers of primate brain evolution, the present study provides renewed support for the social brain hypothesis and suggests that the social brain plastically responds to group size. Many factors may well influence brain size, yet accumulating evidence demonstrates that the complexity of social life is an important determinant of brain size in primates.

Do guide dogs have culture?

Abstract: In the study of animal behaviour, culture is often seen as the result of direct social transmission from a model to a conspecific. In this essay, we show that unrecognised cultural phenomena are sustained by a special form of indirect social learning (ISL). ISL occurs when an individual B learns a behaviour from an individual A through something produced by A. A’s behavioural products can be chemicals, artefacts, but also, we argue, behaviours of another group or species that are the consequence of A’s actions. For instance, a behaviour —guiding a blind person— can be transmitted from dog A to dog B, because the fact that dog A learns the behaviour creates in the mind of the trainer representations about the efficacy of the training practice that can be transmitted to another human, who can then train dog B. These dog behaviours have all the properties of standard cultural behaviours and spread in some dog populations through the exploitation of the social learning capacities of another group/species. Following this idea requires a change in perspective on how we see the social transmission of behaviours and brings forward the fact that certain cultural practices can spread among animals through a cultural co-evolutionary dynamic with humans or other animals.

Measuring social networks in primates: wearable sensors versus direct observations

Abstract: Network analysis represents a valuable and flexible framework to understand the structure of individual interactions at the population level in animal societies. The versatility of network representations is moreover suited to different types of datasets describing these interactions. However, depending on the data collection method, different pictures of the social bonds between individuals could a priori emerge.

Understanding how the data collection method influences the description of the social structure of a group is thus essential to assess the reliability of social studies based on different types of data. This is however rarely feasible, especially for animal groups, where data collection is often challenging.

Here, we address this issue by comparing datasets of interactions between primates collected through two different methods: behavioural observations and wearable proximity sensors. We show that, although many directly observed interactions are not detected by the sensors, the global pictures obtained when aggregating the data to build interaction networks turn out to be remarkably similar. Moreover, sensor data yield a reliable social network over short time scales and can be used for long-term studies, showing their important potential for detailed studies of the evolution of animal social groups.

Detecting social (in) stability in primates from their temporal co-presence network

Abstract: The stability of social relationships is important to animals living in groups, and social network analysis provides a powerful tool to help characterize and understand their (in)stability and the consequences at the group level. However, the use of dynamic social networks is still limited in this context because it requires long-term social data and new analytical tools. Here, we studied the dynamic evolution of a group of 29 Guinea baboons, Papio papio, using a data set of automatically collected cognitive tests comprising more than 16 million records collected over 3 years. We first built a monthly aggregated temporal network describing the baboon’s co-presence in the cognitive testing booths. We then used a null model, considering the heterogeneity in the baboons’ activity, to define both positive (association) and negative (avoidance) monthly networks. We tested social balance theory by combining these positive and negative social networks. The results showed that the networks were structurally balanced and that newly created edges also tended to preserve social balance. We then investigated several network metrics to gain insights into the individual level and group level social networks’ long-term temporal evolution. Interestingly, a measure of similarity between successive monthly networks was able to pinpoint periods of stability and instability and to show how some baboons’ ego-networks remained stable while others changed radically. Our study confirms the prediction of social balance theory but also shows that large fluctuations in the numbers of triads may limit its applicability to study the dynamic evolution of animal social networks. In contrast, the use of the similarity measure proved to be very versatile and sensitive in detecting relationships’ (in)stabilities at different levels. The changes we identified can be linked, at least in some cases, to females changing primary male, as observed in the wild.

Obstacles to the spread of unintuitive beliefs

Abstract: Many socially significant beliefs are unintuitive, from the harmlessness of GMOs to the efficacy of vaccination, and they are acquired via deference toward individuals who are more confident, more competent or a majority. In the two-step flow model of communication, a first group of individuals acquires some beliefs through deference and then spreads these beliefs more broadly. Ideally, these individuals should be able to explain why they deferred to a given source – to provide arguments from expertise – and others should find these arguments convincing. We test these requirements using a perceptual task with participants from the US and Japan. In Experiment 1, participants were provided with first-hand evidence that they should defer to an expert, leading a majority of participants to adopt the expert’s answer. However, when attempting to pass on this answer, only a minority of those participants used arguments from expertise. In Experiment 2, participants receive an argument from expertise describing the expert’s competence, instead of witnessing it first-hand. This leads to a significant drop in deference compared with Experiment 1. These experiments highlight significant obstacles to the transmission of unintuitive beliefs.

High-fidelity copying is not necessarily the key to cumulative cultural evolution

Abstract: The unique cumulative nature of human culture has often been explained by high-fidelity copying mechanisms found only in human social learning. However, transmission chain experiments in human and non-human primates suggest that cumulative cultural evolution (CCE) might not necessarily depend on high-fidelity copying after all. In this study, we test whether defining properties of CCE can emerge in a non-copying task. We performed transmission chain experiments in Guinea baboons and human children where individuals observed and produced visual patterns composed of four squares on touchscreen devices. In order to be rewarded, participants had to avoid touching squares that were touched by a previous participant. In other words, they were rewarded for innovation rather than copying. Results nevertheless exhibited fundamental properties of CCE: an increase over generations in task performance and the emergence of systematic structure. However, these properties arose from different mechanisms across species: children, unlike baboons, converged in behaviour over generations by copying specific patterns in a different location, thus introducing alternative copying mechanisms into the non-copying task. In children, prior biases towards specific shapes led to convergence in behaviour across chains, while baboon chains showed signs of lineage specificity. We conclude that CCE can result from mechanisms with varying degrees of fidelity in transmission and thus that high-fidelity copying is not necessarily the key to CCE.

Handedness in monkeys reflects hemispheric specialization within the central sulcus. An in vivo MRI study in right- and left-handed olive baboons

Abstract: Handedness, one of the most prominent expressions of laterality, has been historically considered unique to human. This noteworthy feature relates to contralateral inter-hemispheric asymmetries in the motor hand area following the mid-portion of the central sulcus. However, within an evolutionary approach, it remains debatable whether hand preferences in nonhuman primates are associated with similar patterns of hemispheric specialization. In the present study conducted in Old world monkeys, we investigate anatomical asymmetries of the central sulcus in a sample of 86 olive baboons (Papio anubis) from in vivo T1 anatomical magnetic resonance images (MRI). Out of this sample, 35 individuals were classified as right-handed and 28 as left-handed according to their hand use responses elicited by a bimanual coordinated tube task. Here we report that the direction and degree of hand preference (left or right), as measured by this manual task, relates to and correlates with contralateral hemispheric sulcus depth asymmetry, within a mid-portion of the central sulcus. This neuroanatomical manifestation of handedness in baboons located in a region, which may correspond to the motor hand area, questions the phylogenetic origins of human handedness that may date back to their common ancestor, 25–40 millions years ago.

The baboon: A model for the study of language evolution

Abstract: Comparative research on the origins of human language often focuses on a limited number of language related cognitive functions or anatomical structures that are compared across species. The underlying assumption of this approach is that a single or a limited number of factors may crucially explain how language appeared in the human lineage. Another potentially fruitful approach is to consider human language as the result of a (unique) assemblage of multiple cognitive and anatomical components, some of which are present in other species. This paper is a first step in that direction. It focuses on the baboon, a non-human primate that has been studied extensively for years, including several brain, anatomical, cognitive and cultural dimensions that are involved in human language. This paper presents recent data collected on baboons regarding (1) a selection of domain-general cognitive functions that are core functions for language, (2) vocal production, (3) gestural production and cerebral lateralization, and (4) cumulative culture. In all these domains, it shows that the baboons share with humans many cognitive or brain mechanisms which are central for language. Because of the multidimensionality of the knowledge accumulated on the baboon, that species is an excellent nonhuman primate model for the study of the evolutionary origins of language.

The repeatability of cognitive performance: a meta-analysis

Abstract: Selection acts on heritable individual variation in behaviours. Both behavioural and cognitive processes play important roles in mediating an individual’s interactions with their environment. Yet, while there is a vast literature on repeatable individual differences in behaviour, relatively little is known about the repeatability of cognitive performance. To further our understanding of the evolution of cognition we gathered 44 datasets on individual performances of 25 species

60 and used meta-analysis to evaluate whether cognitive performance is repeatable across six animal classes. We assessed repeatability (R) in performance (1) on the same task presented at different time intervals (temporal repeatability), and (2) on different tasks that measure the same putative cognitive ability (contextual repeatability). We also addressed whether R estimates are influenced by seven extrinsic factors (moderators): type of cognitive task, type of measurement, delay between tasks, origin of the subjects, experimental context, taxonomic class and if the R value was published or unpublished. We found support for both temporal and contextual repeatability of individual variation in cognitive performance, with significant mean R estimates ranging between 0.15 and 0.28. R estimates were mostly influenced by the type of cognitive performance measures and the fact that R values was published, none of the other moderators showed consistent and significant impacts on repeatability estimates. Our overall findings highlight the widespread occurrence of consistent inter-individual variation in cognition which, like behaviour, may have fitness implications.

Convergent transformation and selection in cultural evolution

Abstract: In biology, natural selection is the main explanation of adaptations and it is an attractive idea to think that an analogous force could have the same role in cultural evolution. In support of this idea, all the main ingredients for natural selection have been documented in the cultural domain. However, the changes that occur during cultural transmission typically result in convergent transformation, non-random cultural modifications, casting some doubts on the importance of natural selection in the cultural domain. To progress on this issue more empirical research is needed. Here, using nearly half a million experimental trials performed by a group of baboons (Papio papio), we simulate cultural evolution under various conditions of natural selection and do an additional experiment to tease apart the role of convergent transformation and selection. Our results confirm that transformation strongly constrain the variation available to selection and therefore strongly limit its impact on cultural evolution. Surprisingly, in our study, transformation also enhances the effect of selection by stabilising cultural variation. We conclude that, in culture, selection can change the evolutionary trajectory substantially in some cases, but can only act on the variation provided by (typically biased) transformation.

Action-matching biases in monkeys

Abstract: Stimulus–response (S–R) compatibility effects occur when observing certain stimuli facilitate the performance of a related response and interfere with performing an incompatible or different response. Using stimulus–response action pairings, this phenomenon has been used to study imitation effects in humans, and here we use a similar procedure to examine imitative biases in nonhuman primates. Eight capuchin monkeys (Sapajus spp.) were trained to perform hand and mouth actions in a stimulus–response compatibility task. Monkeys rewarded for performing a compatible action (i.e., using their hand or mouth to perform an action after observing an experimenter use the same effector) performed significantly better than those rewarded for incompatible actions (i.e., performing an action after observing an experimenter use the other effector), suggesting an initial bias for imitative action over an incompatible S–R pairing. After a predetermined number of trials, reward contingencies were reversed; that is, monkeys initially rewarded for compatible responses were now rewarded for incompatible responses, and vice versa. In this 2nd training stage, no difference in performance was identified between monkeys rewarded for compatible or incompatible actions, suggesting any imitative biases were now absent. In a 2nd experiment, 2 monkeys learned both compatible and incompatible reward contingencies in a series of learning reversals. Overall, no difference in performance ability could be attributed to the type of rule (compatible–incompatible) being rewarded. Together, these results suggest that monkeys exhibit a weak bias toward action copying, which (in line with findings from humans) can largely be eliminated through counterimitative experience.

Other better vs. self better in baboons

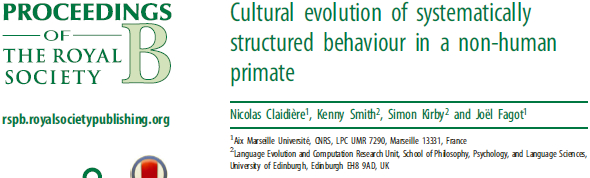

Abstract: Comparing oneself with others is an important characteristic of human social life, but the link between human and non-human forms of social comparison remains largely unknown. The present study used a computerized task presented in a social context to explore psychological mechanisms supporting social comparison in baboons and compare major findings with those usually observed in humans. We found that the effects of social comparison on subject’s performance were guided both by similarity (same vs different sex) and task complexity. Comparing oneself with a better off other (upward comparison) increased performance when the other was similar rather than dissimilar, and a reverse effect was obtained when the self was better (downward comparison). Furthermore, when the other was similar, upward comparison led to a better performance than downward comparison. Interestingly, the beneficial effect of upward comparison on baboons’ performance was only observed during simple task. Our results support the hypothesis of shared social comparison mechanisms in human and nonhuman primates.

Figure 2. (a) Estimated differences in reaction times from the averaged model for the three explanatory variables, task complexity (simple versus complex), comparison (downward/self better versus upward/other better) and similarity (same sex versus different sex). Error bars represent standard errors. Horizontal bars indicate a significant difference between the two conditions. (b) For comparison purposes, this graph illustrates the main results of Tesser et al.’s study on social comparison effects in humans [8].

Argumentation and the Diffusion of Counter-Intuitive Beliefs

Abstract: Research in cultural evolution has focused on the spread of intuitive or minimally counterintuitive beliefs. However, some very counterintuitive beliefs can also spread successfully, at least in some communities—scientific theories being the most prominent example. We suggest that argumentation could be an important factor in the spread of some very counterintuitive beliefs. A first experiment demonstrates that argumentation enables the spread of the counterintuitive answer to a reasoning problem in large discussion groups, whereas this spread is limited or absent when participants can show their answers to each other but cannot discuss. A series of experiments using the technique of repeated transmission show that, in the case of the counterintuitive belief studied: (a) arguments can help spread this belief without loss; (b) conformist bias does not help spread this belief; and (c) authority or prestige bias play a minimal role in helping spread this belief. Thus, argumentation seems to be necessary and sufficient for the spread of some counterintuitive beliefs.

Diffusion of a counter-intuitive answer (green) in groups that initially give mostly the intuitive wrong answer (red). The size of the node represents the confidence of the participants.

Emotion-Cognition Interaction in Nonhuman Primates

Abstract: It is well established that emotion and cognition interact in humans, but such an interaction has not been extensively studied in nonhuman primates. We investigated whether emotional value can affect nonhuman primates’ processing of stimuli that are only mentally represented, not visually available. In a short-term memory task, baboons memorized the location of two target squares of the same color, which were presented with a distractor of a different color. Through prior long-term conditioning, one of the two colors had acquired a negative valence. Subjects were slower and less accurate on the memory task when the targets were negative than when they were neutral. In contrast, subjects were faster and more accurate when the distractors were negative than when they were neutral. Some of these effects were modulated by individual differences in emotional disposition. Overall, the results reveal a pattern of cognitive avoidance of negative stimuli, and show that emotional value alters cognitive processing in baboons even when the stimuli are not physically present. This suggests that emotional influences on cognition are deeply rooted in evolutionary continuity.

Physical intelligence does matter to cumulative technological culture

Abstract: Tool-based culture is not unique to humans, but cumulative technological culture is. The social intelligence hypothesis suggests that this phenomenon is fundamentally based on uniquely human sociocognitive skills (e.g., shared intentionality). An alternative hypothesis is that cumulative technological culture also crucially depends on physical intelligence, which may reflect fluid and crystallized aspects of intelligence and enables people to understand and improve the tools made by predecessors. By using a tool-making– based microsociety paradigm, we demonstrate that physical intelligence is a stronger predictor of cumulative technological performance than social intelligence. Moreover, learners’ physical intelligence is critical not only in observational learning but also when learners interact verbally with teachers. Finally, we show that cumulative performance is only slightly influenced by teachers’ physical and social intelligence. In sum, human technological culture needs “great engineers” to evolve regardless of the proportion of “great pedagogues.” Social intelligence might play a more limited role than commonly assumed, perhaps in tool-use/making situations in which teachers and learners have to share symbolic representations.

Social networks from automated cognitive testing

Abstract: Social network analysis has become a prominent tool to study animal social life, and there is an increasing need to develop new systems to collect social information automatically, systematically, and reliably. Here we explore the use of a freely accessible Automated Learning Device for Monkeys (ALDM) to collect such social information on a group of 22

captive baboons (Papio papio). We compared the social network obtained from the co-presence of the baboons in ten ALDM testing booths to the social network obtained through standard behavioral observation techniques. The results show that the co-presence network accurately reflects the social organization of the group, and also indicate under which conditions the co-presence network is most informative. In particular, the best correlation between the two networks was obtained with a minimum of 40 days of computer records and for individuals with at least 500 records per day. We also show through random permutation tests that the observed correlations go beyond what would be observed by simple synchronous activity, to reflect a preferential choice of closely located

testing booths. The use of automatized cognitive testing therefore presents a new way of obtaining a large and regular amount of social information that is necessary to develop social network analysis. It also opens the possibility of studying dynamic changes in network structure with time and in relation to the cognitive performance of individuals.

Mutual medication in capuchin monkeys

Watch the beautiful video: Monkey medicine

Abstract: Wild and captive capuchin monkeys will anoint themselves with a range of strong smelling substances including millipedes, ants, limes and onions. Hypotheses for the function of the behaviour range from medicinal to social. However, capuchin monkeys may anoint in contact with other individuals, as well as individually. The function of social anointing has also been explained as either medicinal or to enhance social bonding. By manipulating the abundance of an anointing resource given to two groups of tufted capuchins, we tested predictions derived from the main hypotheses for the functions of anointing and in particular, social anointing. Monkeys engaged in individual and social anointing in similar proportions when resources were rare or common, and monkeys holding

resources continued to join anointing groups, indicating that social anointing has functions beyond that of gaining access to resources. The distribution of individual and social anointing actions on the monkeys’ bodies supports a medicinal function for both individual and social anointing, that requires no additional social bonding hypotheses. Individual anointing targets hard-to-see body parts that are harder to groom, whilst social anointing targets hard-to-reach body parts. Social anointing in capuchins is a form of mutual medication that improves coverage of topically applied anti-parasite medicines.

Assessment of Social Cognition in Non-human Primates Using a Network of Test Systems

Abstract: Fagot & Paleressompoulle1 and Fagot & Bonte2 have published an automated learning device (ALDM) for the study of cognitive abilities of monkeys maintained in semi-free ranging conditions. Data accumulated during the last five years have consistently demonstrated the efficiency of this protocol to investigate individual/physical cognition in monkeys, and have further shown that this procedure reduces stress level during animal testing3. This paper demonstrates that networks of ALDM can also be used to investigate different facets of social cognition and in-group expressed behaviors in monkeys, and describes three illustrative protocols developed for that purpose. The first study demonstrates how ethological assessments of social behavior and computerized assessments of cognitive performance could be integrated to investigate the effects of socially exhibited moods on the cognitive performance of individuals. The second study shows that batteries of ALDM running in parallel can provide unique information on the influence of the presence of others on task performance. Finally, the last study shows that networks of ALDM test units can also be used to study issues related to social transmission and cultural evolution. Combined together, these three studies demonstrate clearly that ALDM testing is a highly promising experimental tool for bridging the gap in the animal literature between research on individual cognition and research on social cognition.

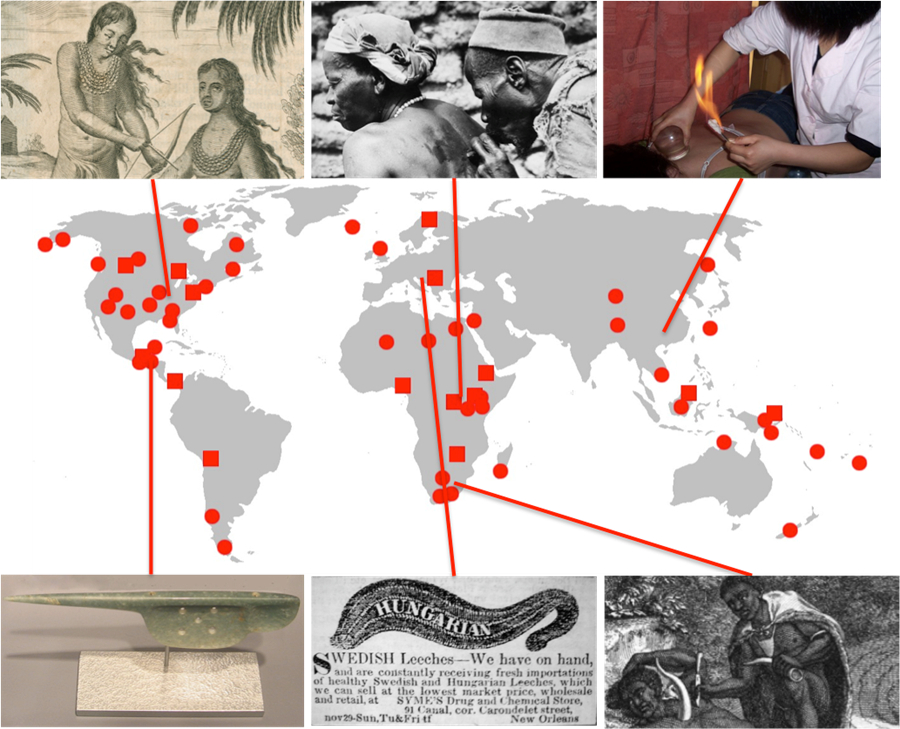

Universal Cognitive Mechanisms Explain the Cultural Success of Bloodletting

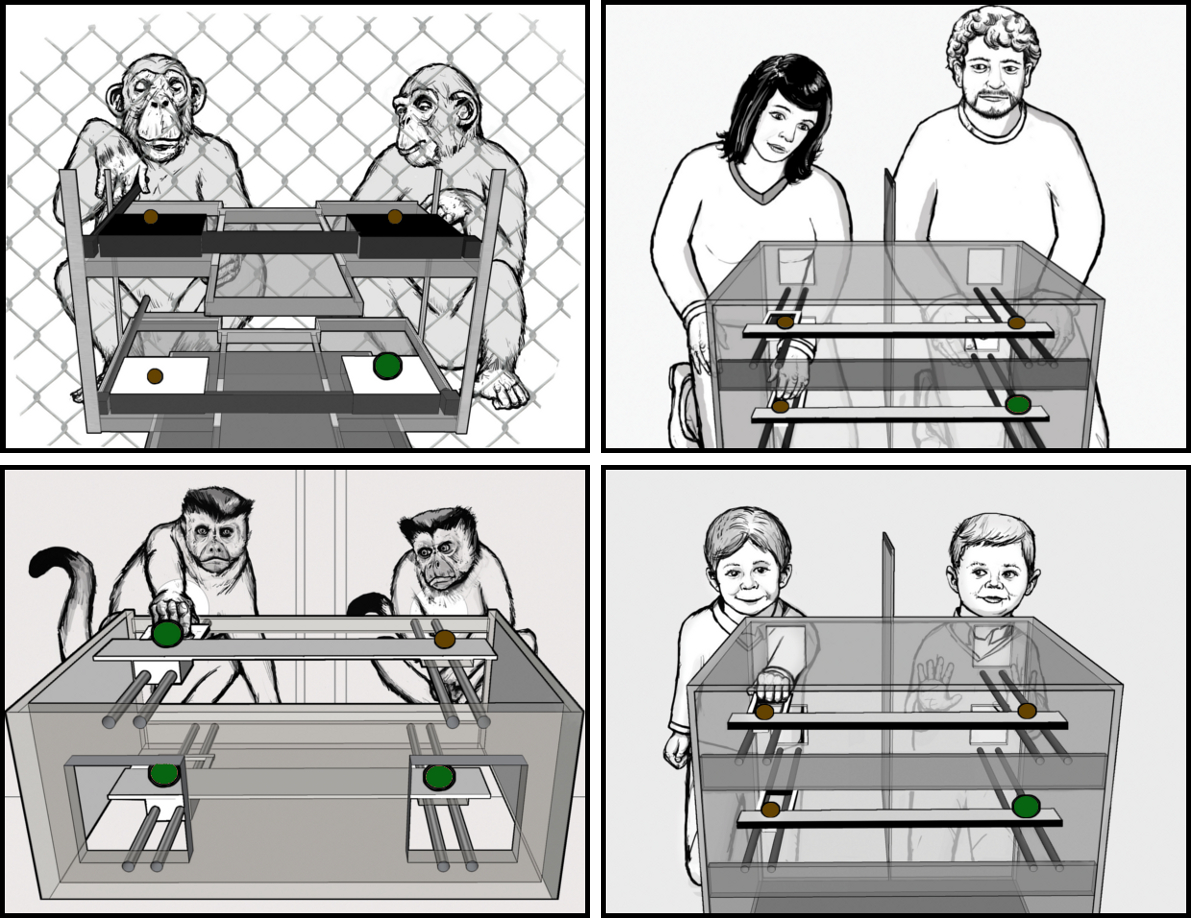

Selective and contagious prosocial resource donation in capuchin monkeys, chimpanzees and humans

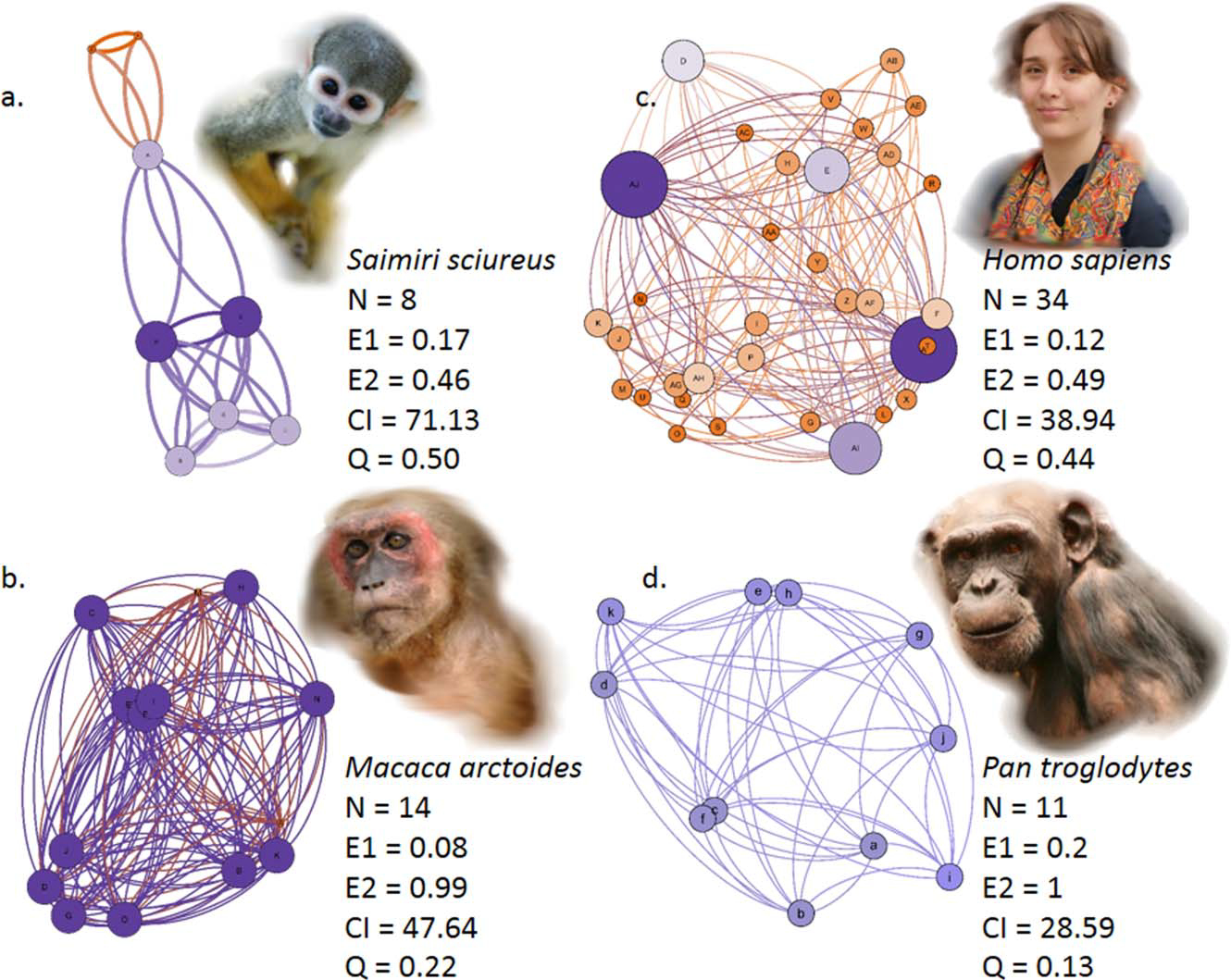

Social networks in primates: smart and tolerant species have more efficient networks

Pasquaretta, C., Leve, M., Claidiere, N., van de Waal, E., Whiten, A., MacIntosh, A. J. J., . . . Sueur, C. (2014). Social networks in primates: smart and tolerant species have more efficient networks. Sci. Rep., 4. doi: 10.1038/srep07600

Pasquaretta, C., Leve, M., Claidiere, N., van de Waal, E., Whiten, A., MacIntosh, A. J. J., . . . Sueur, C. (2014). Social networks in primates: smart and tolerant species have more efficient networks. Sci. Rep., 4. doi: 10.1038/srep07600

Wild vervet monkeys copy alternative methods for opening an artificial fruit

Abstract: Experimental studies of animal social learning in the wild remain rare, especially those that employ the most discriminating tests in which alternative means to complete naturalistic tasks are seeded in different groups. We applied this approach to wild vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops) using an artificial fruit (‘vervetable’) opened by either lifting a door panel or sliding it left or right. In one group, a trained model lifted the door, and in two others, the model slid it either left or right. Members of each group then watched their model before being given access to multiple baited vervetables with all opening techniques possible. Thirteen of these monkeys opened vervetables, displaying a significant tendency to use the seeded technique on their first opening and over the course of the experiment. The option preferred in these monkeys’ first successful manipulation session was also highly correlated with the proportional frequency of the option they had previously witnessed. The social learning effects thus documented go beyond mere stimulus enhancement insofar as the same door knob was grasped for either technique. Results thus suggest that through imitation, emulation or both, new foraging techniques will spread across groups of wild vervet monkeys to create incipient foraging traditions.

Cultural evolution of systematically structured behaviour in a non-human primate

Claidière, N., Smith, K., Kirby, S., & Fagot, J. (2014). Cultural evolution of systematically structured behaviour in a non-human primate. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1797). doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1541

Claidière, N., Smith, K., Kirby, S., & Fagot, J. (2014). Cultural evolution of systematically structured behaviour in a non-human primate. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1797). doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1541

In the media:

BBC News: Baboons may share human ability to build on work of others

Hufftington Post: The ‘Human’ Quality We Share With Baboons

In French:

Pour la Science: La culture cumulative n’est pas le propre de l’homme

Science et Avenir: Le babouin s’améliore de génération en génération

Radio Canada: La culture cumulative n’est pas unique à l’homme

Frequency of Behavior Witnessed and Conformity in an Everyday Social Context

Abstract: Conformity is thought to be an important force in human evolution because it has the potential to stabilize cultural homogeneity within groups and cultural diversity between groups. However, the effects of such conformity on cultural and biological evolution will depend much on the particular way in which individuals are influenced by the frequency of alternative behavioral options they witness. In a previous study we found that in a natural situation people displayed a tendency to be ‘linear-conformist’. When visitors to a Zoo exhibit were invited to write or draw answers to questions on cards to win a small prize and we manipulated the proportion of text versus drawings on display, we found a strong and significant effect of the proportion of text displayed on the proportion of text in the answers, a conformist effect that was largely linear with a small non-linear component. However, although this overall effect is important to understand cultural evolution, it might mask a greater diversity of behavioral responses shaped by variables such as age, sex, social environment and attention of the participants. Accordingly we performed a further study explicitly to analyze the effects of these variables, together with the quality of the information participants’ responses made available to further visitors. Results again showed a largely linear conformity effect that varied little with the variables analyzed.

How Darwinian is cultural evolution?

Abstract: Darwin-inspired population thinking suggests approaching culture as a population of items of different types, whose relative frequencies may change over time. Three nested subtypes of populational models can be distinguished: evolutionary, selectional and replicative. Substantial progress has been made in the study of cultural evolution by modelling it within the selectional frame. This progress has involved idealizing away from phenomena that may be critical to an adequate understanding culture and cultural evolution, particularly the constructive aspect of the mechanisms of cultural transmission. Taking these aspects into account, we describe cultural evolution in terms of cultural attraction, which is populational and evolutionary, but only selectional under certain circumstances. As such, in order to model cultural evolution, we must not simply adjust existing replicative or selectional models, but we should rather generalize them, so that, just as replicator-based selection is one form that Darwinian selection can take, selection itself is one of several different forms that attraction can take. We present an elementary formalization of the idea of cultural attraction.

Diffusion Dynamics of Socially Learned Foraging Techniques in Squirrel Monkeys

Abstract: Social network analyses [1–5] and experimental studies of social learning [6–10] have each become important domains of animal behavior research in recent years yet have remained largely separate. Here we bring them together, providing the first demonstration of how social networks may shape the diffusion of socially learned foraging techniques [11]. One technique for opening an artificial fruit was seeded in the dominant male of a group of squirrel monkeys and an alternative technique in the dominant male of a second group. We show that the two techniques spread preferentially in the groups in which they were initially seeded and that this process was influenced by monkeys’ association patterns. Eigenvector centrality predicted both the speed with which an individual would first succeed in opening the artificial fruit and the probability that they would acquire the cultural variant seeded in their group. These findings demonstrate a positive role of social networks in determining how a new foraging technique diffuses through a population.

Claidière, N., Scott-Phillips, T. C., & Sperber, D. (2014). How Darwinian is cultural evolution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0368

Claidière, N., Scott-Phillips, T. C., & Sperber, D. (2014). How Darwinian is cultural evolution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0368